THE 3 ETHICS OF PERMACULTURE

Fair Share

Set limits to population & consumption and share the surplus. “There is enough for everyone’s needs but not everyone’s greed.” Mahatma Gandhi

Many people think of Permaculture as just a fancy form of gardening. However Permaculture looks at both human and natural systems as inseparable from each other. All three of the Permaculture Ethics must be equally considered and attended to for any system to truly thrive.

Earth Care

All species including our own rely on ecosystem services to survive and thrive. We must protect and repair the land before it is too late.

People Care

We can only be as safe and healthy as the society we create and live in. We must care for each other to prosper together.

THE 12 PRINCIPLES OF PERMACULTURE

Rather than a set of ‘rules’, all the lessons of Permaculture are held within these twelve deceptively simple principles. Each statement contains a wealth of knowledge, full of practical and philosophical wisdom which is common to Indigenous cultures all over the world.

Each principle unfolds more and more upon examination. For instance, ‘Integrate rather than segregate ’ is a warning against the dangers of monocultures, at the same time as being a reminder to unite people of all different walks of life. ‘Use edges and value the marginal’ refers not just to the richness of natural resources that occurs on the borders of ecosystems, for instance between a creek and its bank, but also refers to the value of marginalised communities; some of the most thriving permaculture projects in the world have been in low socio-economic areas.

Click on each title below to learn more about these rich and fascinating ideas, and how you can apply them in your daily life. The links below are to the ‘Permaculture Principles’ website, which we acknowledge with gratitude.

THE PERMACULTURE DESIGN COURSE

The Standard PDC

Mollison began teaching permaculture in January 1981 when his first Permaculture Design Course was run over 140 hours in Victoria. It quickly consolidated into a two-week intensive 72-hour course with an established curriculum to produce trainee designers. Completion of a PDC became the entry point to the developing permaculture profession and the right to use the term “permaculture” was vested by Mollison in the graduates of these courses.

A special PDC for South-Eastern Australia

In the mid 1990’s permaculture educators associated with Permaculture Melbourne began offering extended part-time PDCs. These gradually increased in length to cater for the new ideas coming through the movement, to provide more background on ecological processes and more opportunity to examine bio-regional applications, in addition to the standard 72-hour curriculum. The resulting syllabus that has been developed for teaching permaculture in temperate south-eastern Australia now requires a minimum 100 hours of student contact to deliver.

Going Mainstream

In the early 2000’s work began on the development of a competency-based Accredited Permaculture Training package through the national TAFE system to enable students to gain qualifications that could be recognised for employment purposes. These qualifications through Certificates I to IV and a Diploma at level V incorporate the PDC curriculum, extended to provide measurable competency-based skills.

Notwithstanding the availability of TAFE and some university-level permaculture courses, the PDC remains an extremely popular and empowering entry to the permaculture movement.

THE HISTORY OF PERMACULTURE

It initially focused on agriculture

“Permaculture is a design system for creating sustainable human environments” (Mollison and Slay, 2000). The Permaculture concept was developed in Tasmania during the 1970’s as a collaborative effort between Australians Bill Mollison and David Holmgren. They coined the word permaculture as a contraction of “permanent agriculture”.

Whilst acknowledging that “normal gardening for annuals is part of a permacultural system” the focus of Permaculture One was on perennial, tree-based cropping systems.

It soon became apparent that permaculture had applications beyond the perennial polyculture “Food Forest” concept. A decade on, in his encyclopaedic publication Permaculture: a Designer’s Manual, Mollison described permaculture as “… the conscious design and maintenance of agriculturally productive ecosystems which have the diversity, stability and resilience of natural ecosystems, it is the harmonious integration of landscape and people providing their food, energy, shelter, and other material and non-material needs in a sustainable way.”

From agriculture to culture

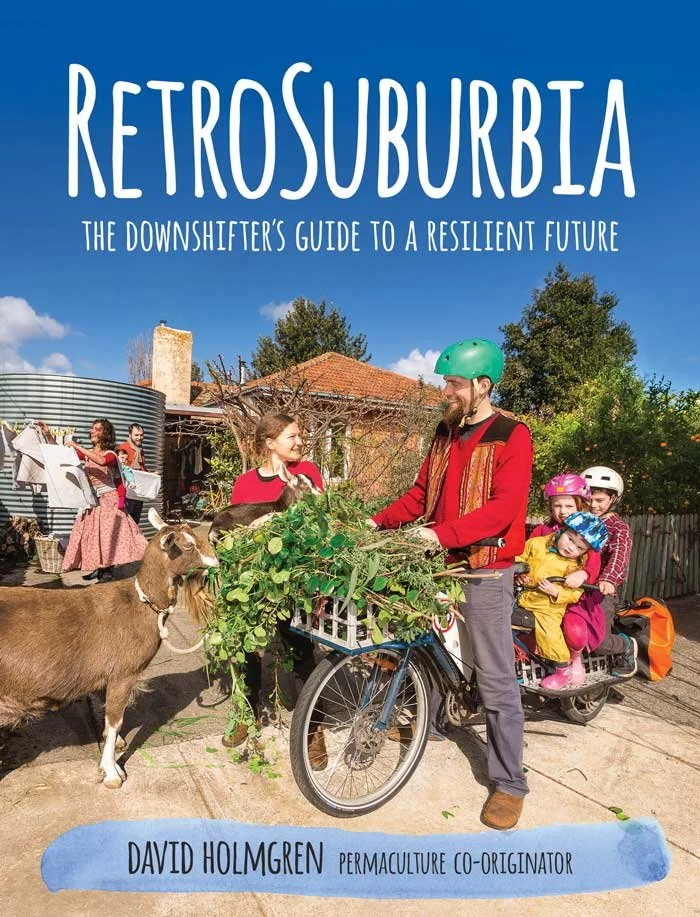

Despite the focus on design in that statement, permaculture has continued to be viewed in terms of productive landscapes. In his definitive update of permaculture for the 21st century, Permaculture Principles and Pathways Beyond Sustainability, David Holmgren* summarised the then current visionary view of permaculture as “Consciously designed landscapes which mimic the patterns and relationships found in nature, while yielding an abundance of food, fibre and energy for provision of local needs. People, their buildings and the ways they organise themselves are central to permaculture” but he also pointed-out that “permaculture is not the landscape” and that he saw permaculture as “… the use of systems thinking and design principles that provide the organising framework for implementing the above vision”.

Of course, all of Permaculture is based on principles and practices that have been implemented by Indigenous cultures all around the world for thousands of years, and everyone who enacts Permaculture knowledge owes a debt of gratitude to Indigenous cultures.

Dave Jacke was the first author to set-out a clear step-by-step design process for permaculture design and his ideas are being widely adopted today. As a design process, it has practical applications in the design of not just our landscapes, but also our societies and built environment as well. In keeping with that broadening of its application, the term itself is now seen to represent “permanent culture” rather than “permanent agriculture”.

*David Holmgren runs monthly site tours of his home property ‘Melliodora’ which members of the public can attend. Please click here to find out more.